Wintering

We're at the tail end of winter right now; it's the second day of March with extremely high winds that started last night. I live on the top floor of a condo and the shrieking wind is still shaking the building and kept me up all night. I'm at home today with my son since schools and offices are all closed due to the dangerous weather conditions.

I was looking through my files and I found something that I wrote almost ten years ago, about Sylvia Plath.

March 24, 2009

Sylvia Plath’s son Nicholas committed suicide the other day in Alaska. I had just finished reading Wintering, which makes his death even more poignant.

Kate Moses’ first novel, Wintering, develops a portrait of Sylvia Plath as mother, wife, and poet, in that order. She is depicted as a devoted mother and highly domesticated wife who sews, cooks, and gardens, the details of such are masterfully written. Moses recreated Court Green, the country home of the Hughes’, with her potatoes, apples, onions, honey bees, and daffodils. These are the most solid images in the novel, the objects that Sylvia most wants to hold onto amid her marriage and life dissolving. She begs Ted, her husband, to return to Court Green for her harvested items, for they seem to her all that she has to show for her life there. These items are solid, vivid, and clutched to her bosom in such a way that they feel solid and precious to the reader as well.

The book is divided up by Sylvia’s poems as chapter titles in chronological order that they were written, but with the narrative out of order, going back and forth from America, the countryside at Court Green, and various London flats. The poems eventually make up the collection titled Ariel, which Ted Hughes published after Sylvia’s death. The story and the poems get more desperate and sharp as the narrative unfolds, a sharp as the knife that Sylvia accidentally cuts her thumb on.

Because the children are so young, Sylvia seems mostly alone in contemplative solitude. She keeps her hands busy making clothes for the children, baking, gardening, and painting the walls of her London flat. She writes feverishly in her spare moments, on the back of her manuscript for The Bell Jar. It’s as if she knows that what she has is precious, alive, and burning. It is eventually what will burn her alive.

This novel is as intricate as a spider’s web, heartbreaking, profound, and beautiful. It is indeed as precious as the jars of honey that Sylvia horded for the winter, waiting for a spring that would never come for her.

I wrote the following poem while studying abroad at St. Andrews University in Scotland during the second semester of my junior year in college.

Sylvia Plath 1932-1963

The ocean is weeping, mourning

for her aborted children, shedding

the uterine lining from her fertile womb.

I run along, crushing the exoskeletons

of souls dried out by the sun;

I am making the sand for the beach with my feet.

Glittering gold, Midas touch.

The ocean’s tears carve out ribs into the sand,

scraping skeletons into the crushed bone.

Seagulls strewn along my path.

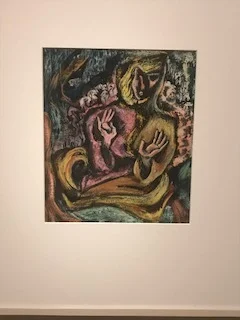

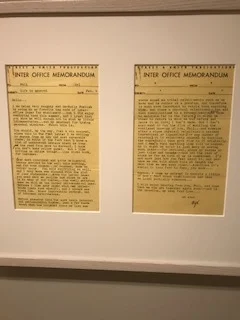

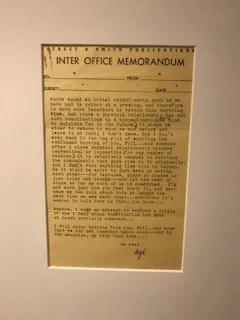

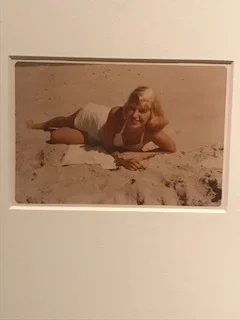

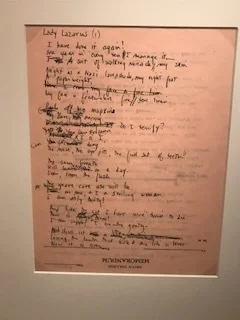

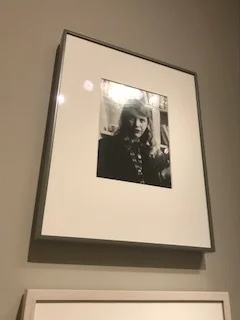

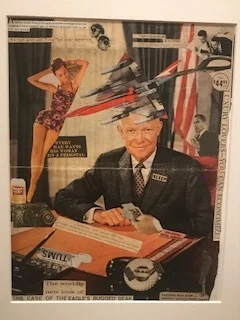

Last summer I went to see a small exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery featuring Sylvia Plath's paintings, letters, and various other artifacts. Here are some of the photographs I took of the exhibit.